Truth: in 1000 words or less

Steven A. Craig

The Not So Friendly Skies

When is a contract not really a contract? When you are dealing with the airlines, of course! Imagine for a moment that you and I enter a contract to paint your house. We agree on a price and timing, but after the check has cleared the bank, I inform you that I’m actually going to wait until next Summer to do the job. Or consider for a moment what you might do when you book a hotel for you and your family only to arrive at your destination to discover that the hotel sold your room out from under you to a higher bidder. You wouldn’t put up with that duplicity now would you? But for some reason, the airlines get away with it, and federal law allows it.

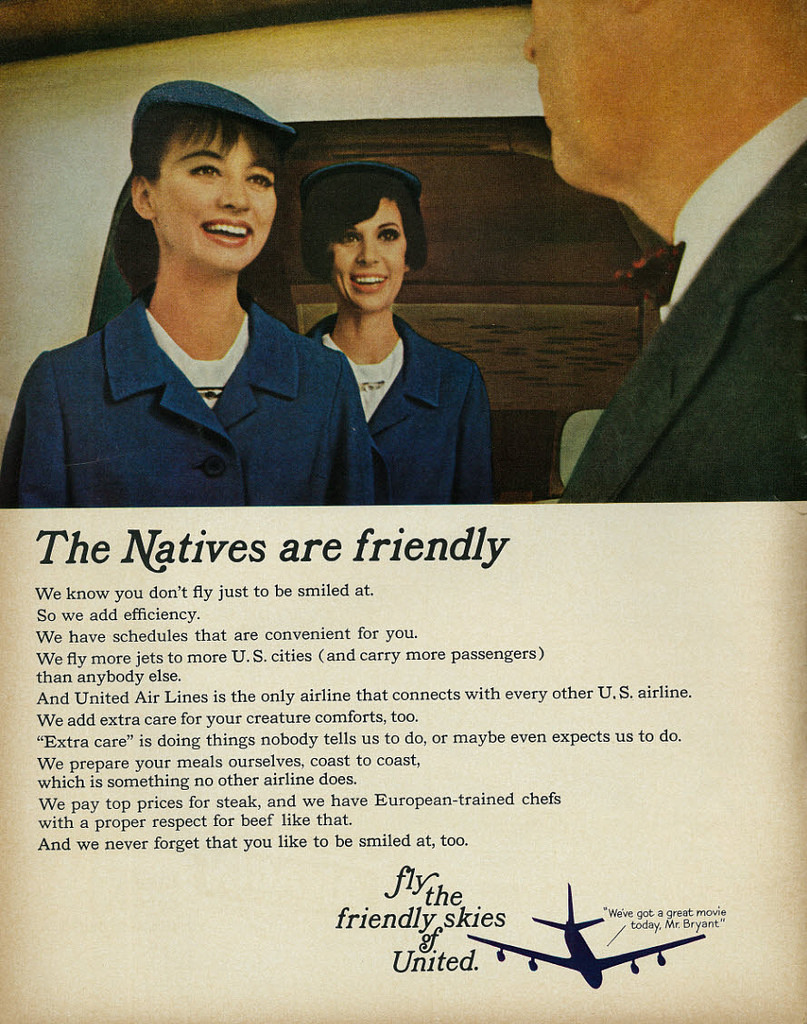

This issue rose to the surface recently with the startling video of United Airlines forcibly removing an Asian doctor from one of their flights even though he had paid for his flight, checked in, and was already seated. Despite his protestations that he needed to get to his destination in order to see clients the next day and his peaceful refusal to leave his seat, they dragged him off the plane, causing injuries that sent the nation into an uproar when video taken by fellow passengers went viral days after the flight. Since then, United’s CEO Oscar Munoz has done more apologizing and backpedaling than a white-robed Klan member unceremoniously dropped into the hostile streets of Compton, but let’s not miss the bigger point here and pin this solely on United. Almost every airline does this, and the federal government lets them.

When I was back in law school, they made us take a class called “Contracts” since, you know, contracts are supposed to be the legally-binding agreements upon which our entire society depends. The essence of contracts is that they are mutually-acceptable and mutually-binding. In other words, they stand to benefit both parties, and both parties have a legal obligation to uphold their end of the bargain. The idea here is that we need to be able to rely on these agreements, and the courts are here to protect us when that somehow goes awry. So why does all contract law get thrown out the window when it comes to the airline industry?

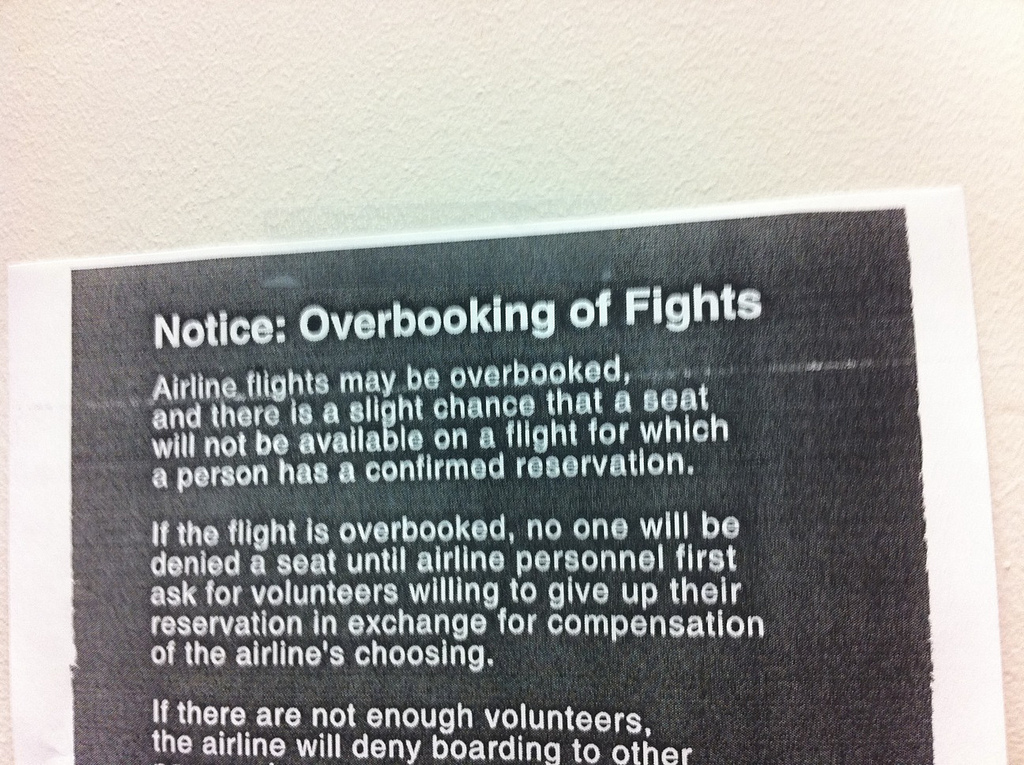

When someone purchases a plane ticket (or any other service for that matter), they are entering into a sort of contract. You pay money for the right to be on a particular flight at a particular time. You rely on this contract so that you can schedule your business appointments and vacation plans accordingly. We all understand that weather or unforeseeable delays may impact our travel plans, but we otherwise expect this contract to be mutually enforceable. As the passenger, you can’t just skip your flight and expect to get on the next one. It doesn’t work that way. But somehow the airlines are permitted to sell more tickets than they have seats and involuntarily bump you from the flight if need be.

When someone purchases a plane ticket (or any other service for that matter), they are entering into a sort of contract. You pay money for the right to be on a particular flight at a particular time. You rely on this contract so that you can schedule your business appointments and vacation plans accordingly. We all understand that weather or unforeseeable delays may impact our travel plans, but we otherwise expect this contract to be mutually enforceable. As the passenger, you can’t just skip your flight and expect to get on the next one. It doesn’t work that way. But somehow the airlines are permitted to sell more tickets than they have seats and involuntarily bump you from the flight if need be.

According to the Transportation Department, this happened to approximately 41,000 domestic passengers last year alone, almost 4000 of them on United Airlines. While this represented only a minimal percentage of about .004 percent of customers, imagine the potential frustration and impact that could occur when you are told you no longer have a seat on the flight you booked over two months in advance. Jobs get lost, business deals fall through, and vacations get ruined by this sort of practice. Yes, the airlines first offer compensation for those who voluntarily give up their seat, but often passengers’ plans are not flexible and taking a later flight is not an option. Sometimes a free flight voucher just isn’t going to cut it.

If no passengers accept the airline’s initial offer, federal regulations allow the airline to select people at random. Yes, they are entitled to compensation (usually about 200% of your fare with a maximum cap of $650), but otherwise they have little recourse for their troubles. Oh and don’t ask about a voucher for food or lodging made necessary by your delay- that’s not included. Next thing you know, you’re sharing a hotel room with John Candy as you wait for the next train back to Chicago.

Listen, I understand why the airlines do this. They are trying to maximize profits by keeping the flight as full as possible. They know a certain number of passengers will simply not show up for their flight, and they use an algorithm to determine the number of redundant seats they can expect to sell. But no other industry gets this luxury. Sometimes people cancel their hotel room at the last minute. That doesn’t mean the hotel industry is permitted to book rooms they have promised to someone else. Every other industry is expected to manage their pricing in a way that allows them to operate at a profit after taking into consideration the obligations they have to the contracts they take on. Shoot, I’m pretty sure I could even make a profit selling VHS tapes to millennials who don’t own a VCR if I were allowed to back out of contracts anytime they become inconvenient and no longer further my interests just as the airline industry is allowed to do.

In fact, a reasonable solution to all this was posited almost thirty years ago by late economist Julian Simon who suggested that overbooked airlines should never be allowed to take a ticketed passenger’s flight involuntarily but rather should be compelled to start an auction for the seat. They would be required to up their financial incentive to voluntarily give up the seat in $100 increments until someone takes them up on the offer. At some point, someone will decide the money outweighs their need to get there at the scheduled time, and then everyone walks away happy, as compared to be dragged through the aisles by the scruff of their shirt.

Steven Craig is the author of the best-selling novel WAITING FOR TODAY, as well as numerous published poems, short stories, and dramatic works. Read his blog TRUTH: in 1000 Words or Less every THURSDAY at www.waitingfortoday.com