Brown is the New Black

by Steven A. Craig

I’m going to preface this story with a brief explanation and appeal for understanding. Colorado, you see, is hardly the most racially diverse state in the nation. In fact, let’s be blunt, shall we? It’s pretty damn white. We may not be as absurdly Caucasian as Vermont, where I spent a couple of years in graduate school, but let’s face it, our racial demographic looks a lot more like a professional hockey team than it does a basketball team. Or to put it another way, we are more jam band and country than we are hip hop and smooth jazz. Either way, we simply don’t have many African-Americans in Colorado.

This context will help mitigate the shock you may have when I relay to you a humorous piece of dialogue I had recently with my ten year old son after picking him up from school. In the course of telling me about his day, in the animated manner we have just come to expect from him, he started to talk about his project partner, “Kay”, a fourth grader whose family was from South Korea. While I let the phrase go the first time I thought I heard it, I could not help but stop him when I heard him say “my black friend” for a second time.

“Buddy, are you talking about Kay when you say your ‘black friend’?”

“Yeah, Dad, he’s black.”

“But Buddy, I thought his parents were from Korea.”

“They are.”

It took me a minute to put it all together, but then I got it. My son, based upon his skin being a bit darker than others, racially classified Kay as “black”. For him, there were, apparently, two racial groups in the entire world: white people and black people, with the latter encompassing everything from Chinese-Americans, to African-Americans, to Inuits for crying out loud. I tried not to bust a gut laughing as I pondered the cultural ramifications of this perception.

Now I have to tell you that my son is no racist. He knows that all human beings are worthy of dignity and respect and that skin color has no bearing whatsoever on a person’s worth. His sense of social justice is as pervasive and genuine as I have ever seen it in a kid his age. With that backdrop then, you can see that his comments reflect a certain sincere innocence regarding the turbulent nature of race as it plays itself out in the tapestry of public American life. What makes it so darn funny is that he doesn’t even get what makes someone “black” or not.

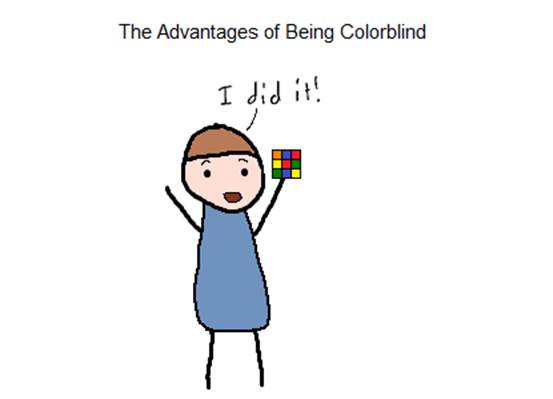

For a moment, I was tempted to let him sit with his misconception. It seemed to me that it represented a naiveté that could not endure but I wanted him to have as long as it could last, like a belief that Santa Claus is real. It was a sort of colorblindness, in the sense that he was unaware of all the social context that color inherently construed to the rest of us. Yes, he saw and understood the differences in skin color, and he knew that people could be treated differently because of it, but his experiences with racism had been so negligible as to render him incapable of deciphering the subtle nuances of racial discrimination.

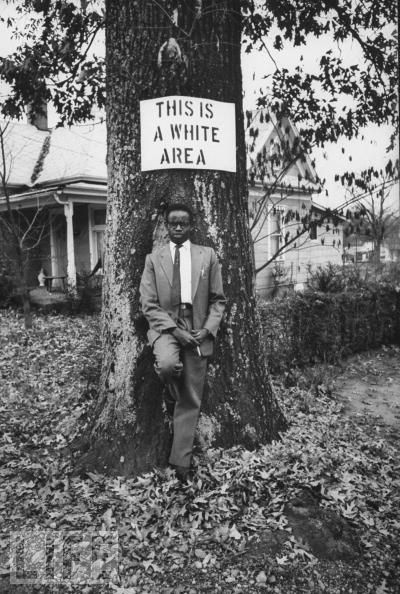

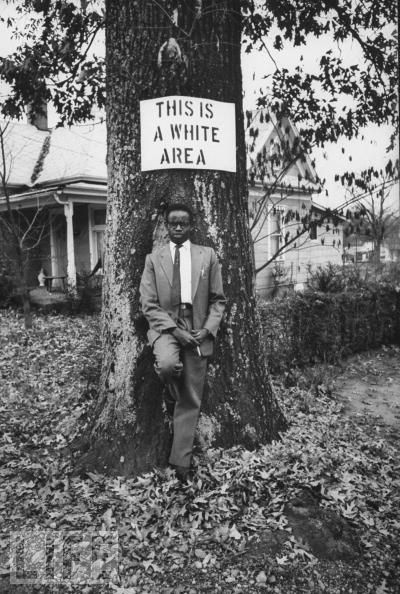

Then I realized that I would being doing him an injustice to let him go forward with this misunderstanding of the social context that informs race relations in America. Kay’s folks, I explained to him, had come here willingly to create a better life for their family, whereas African-Americans were brought here as slaves and forced to work under the most inhumane conditions imaginable. Even to this day, the stereotypes Kay will face will be things like being a smart, math-oriented student and a bad driver, while African-Americans fight a daily struggle against preconceptions of them as uneducated criminals. When Kay gets pulled over in high school he will be no more likely to be harassed by the police than my son will. And we all know the same cannot be said for African-American teenagers.

Then I realized that I would being doing him an injustice to let him go forward with this misunderstanding of the social context that informs race relations in America. Kay’s folks, I explained to him, had come here willingly to create a better life for their family, whereas African-Americans were brought here as slaves and forced to work under the most inhumane conditions imaginable. Even to this day, the stereotypes Kay will face will be things like being a smart, math-oriented student and a bad driver, while African-Americans fight a daily struggle against preconceptions of them as uneducated criminals. When Kay gets pulled over in high school he will be no more likely to be harassed by the police than my son will. And we all know the same cannot be said for African-American teenagers.

In the end, as much as I would have liked to have let him continue to be oblivious to the ugly truth of American racism, I couldn’t just let my son’s seeming colorblindness go. After all, as much as he was innocent in this regard, this is the new American racism, the penchant to turn a blind eye to the social context that informs our race relations. In our haste to proclaim ourselves colorblind, we want to forget all about the history that lingers in the background like the bad horror move villain that keeps coming back no matter how many times the lone survivor thinks they’ve killed him off. But just like a an axe-wielding maniac with a hockey mask, our checkered racial past is something we need to confront rather than ignore.

I’m not saying all white Americans have to make a personal apology to every African-American and start ponying up cash for the massive reparations effort, but we do need to own this. No, White Dude Circa 2017, you are not personally responsible for slavery, but you do need to acknowledge and respect the historical context that your African-American brothers and sisters contend with each and every day of their waking lives. To just turn your head away and cast a cold shoulder to the existence of the latent bias that African-Americans still struggle against, to pretend like it simply isn’t real anymore just because you deemed it so, is to summarily dismiss their experience with an almost willful disregard.

Back when Stephen Colbert still did the Colbert Report, his satirically conservative character used to claim to be “colorblind”, imperceptive of the race relations in America. His satire, like my son’s innocent gesture, reminds us that we cannot afford to turn a blind eye to the truth of our racial past if we are to truly put race behind us going forward. For it is in the fine distinctions of gray that the truths of our social understandings really matter.

Steven Craig is the author of the best-selling novel WAITING FOR TODAY, as well as numerous published poems, short stories, and dramatic works. Read his blog TRUTH: in 1000 Words or Less every THURSDAY at www.waitingfortoday.com